Avoid the expertise performance trap

Contemporary leadership requires expertise to take a back seat.

Decades of discourse around expertise has missed something crucial: when individuals perform expertise, they make the group mediocre.

The credibility game

When they contract a consultant or hire a CEO, Boards want to see a track record. Do you understand their regulatory maze? Have you delivered transformational change before? Have you solved problems exactly like ours before? The whole professional world runs on credentialling - those carefully crafted LinkedIn profiles, the "20 years in healthcare," the "former CEO," the deep sector knowledge claims.

It gets you appointed, earns you the seat at the table … and then rapidly goes downhill.

Harvard Business School's Linda Hill spent years studying innovation in organisations. Her "Collective Genius" research shows innovation emerges from collective creativity, not individual expert leadership. Not from the smartest person in the room having the best idea, but from creating conditions where collective brilliance can emerge.

MIT Sloan Management Review published research showing that problem-solving effectiveness depends more on collaborative processes than individual domain knowledge. Team-based, interdisciplinary approaches consistently outperform single-expert models.

Nancy Kline figured this out decades ago. Her "Time to Think" methodology proved that leaders as "thinking partners" outperform those who lead through expertise display. The magic isn't in having the answers - it's in asking the questions that help others find their answers.

When I fell into my own expertise trap

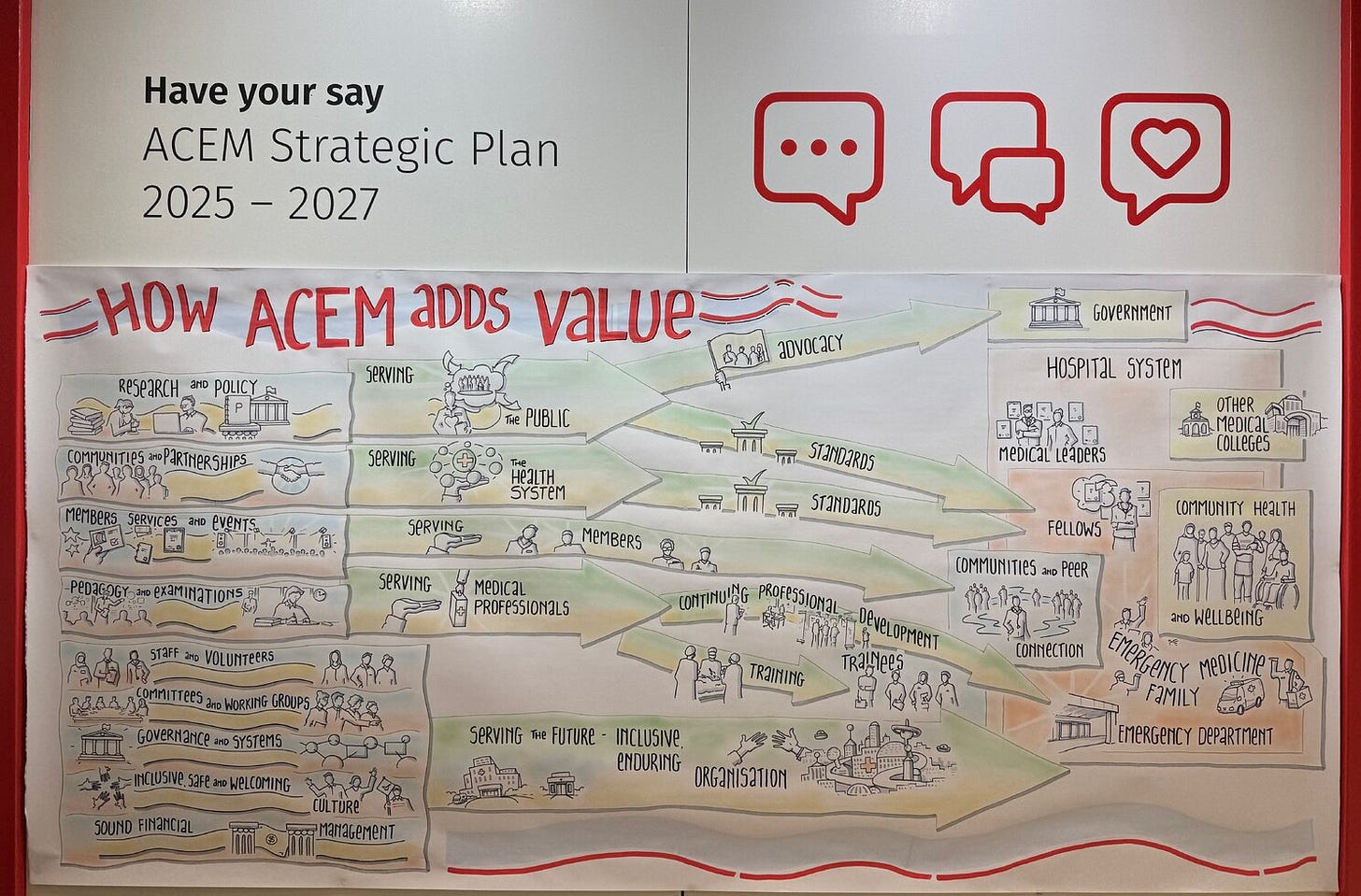

I was working with the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine, helping them develop their 2025-30 strategy. When it came to mapping how the College creates value - what they do, how it flows to different communities, their impact on the world - I got seduced by the expertise in the College that I was developing. I thought the strategy needed to show the complexity - and I think I felt something to prove to these amazing expert physicians: look, I understand you.

So I created this incredibly detailed diagram, full of flows and feedback loops and every groups and stakeholder. It was technically complete. It was also practically useless.

For their annual scientific meeting, I worked with ACEM’s Comms team and a graphic recorder to put this complexity on the wall for everyone to see. Work-in-progress, ready for comment. I knew it needed some simplification, but I thought it first needed validation: is this accurate?

Then a member attending the conference asked a simple question: "Where is the patient in all this?" One question not asked by anyone so far. The entire complex diagram became obviously wrong.

I put the patient in the centre of a circle. Aligned all the college's activities to point inward. Made it about serving the patient, not demonstrating institutional sophistication. The diagram became vastly simpler. And infinitely more useful because it was clear, rather than clever. Not because it demonstrated my expertise, but because it captured theirs.

The credentialling catch-22

The credentials that give you legitimacy can destroy your effectiveness.

If you're the "content expert," people defer rather than contribute their insights. If you're the "strategy expert," they wait for your answers instead of thinking together. The more content authority you establish, the less collective intelligence emerges.

But there aren't many who respond well to "I don't know your industry, but I know how to help you think about your challenges." Expertise positions us to be appointed. And then gets in the way once we are.

What we're afraid of

We perform expertise because we're terrified of being found out: if we don't have the answers, we don't deserve to be there. Questions make us look weak, admitting we don't know makes us look incompetent.

The research suggests exactly the opposite. The courage to be publicly correctable often leads to breakthroughs. Transparency invites the insights that expertise performance shuts down. Questions that help others think beat clever solutions every time.

The ACEM diagram worked precisely because I was willing to be wrong in public. Because I showed my thinking, invited correction, made space for someone else's insight to emerge. The process enabled contribution rather than demanding deference.

A different kind of credibility

The alternative means credentialling differently. Instead of "I know your industry," try "I know how to help you make sense of complexity." Instead of "I've solved this problem before," try "I know how to create conditions where solutions emerge." Instead of demonstrating content expertise, demonstrate process mastery.

Nancy Kline calls it being a "thinking partner" - not an equal expert, but someone whose questions help others think better. Someone expert at enabling other people's brilliance rather than displaying their own.

This isn't about being humble or self-deprecating. Real expertise creates simplicity and enables others, not complexity that impresses. The best solutions often feel obvious in retrospect - not because they're simple, but because they emerge from collective wisdom rather than individual cleverness.

The shift we need

We must move faster from wanting to be the smartest person in the room to becoming the leader that makes everyone in the room smarter. From impressive complexity to useful simplicity. From "I know your answers" to "I believe in your ability to find answers."

It's a fundamental shift in what professional credibility means. Not the depth of your knowledge, but the quality of your questions. Not the sophistication of your frameworks, but your ability to create conditions where breakthrough thinking happens.

The expertise performance trap shows up wherever we prioritise looking smart over being useful. Wherever we choose impressive over effective. Wherever we perform knowledge instead of enabling wisdom.

The way out isn't to abandon expertise - it's to become expert at something different. Expert at creating the conditions where collective intelligence flourishes. Expert at the kind of transparency that invites correction. Expert at asking questions that spark interest rather than glaze eyes.

The people closest to the problem usually have the insights needed for the solution. The leader’s job is to help them be smarter together.

Fin - a lesson in expert humility

I’m very please with the work I did on the Strategy - delivered them a strategy they are pleased with that is shaping their activities, and I learnt lots along the way. New Case Study is on my website if you’re curious.

Of all the things I found out, here is my favourite. Over dinner, I asked a group of College Fellows what they would do if there was a major incident right outside. The answer came quick: whatever we could until the first paramedic arrived, then get to the hospital. I was surprised - wouldn’t you keep helping?

No. We’d get in the paramedics’ way. The are trained to be first responders. We are trained to be second. We begin when they’ve done the stabilisation and triage.

When I expressed surprise that they’d leave a major incident, one gave me a concrete example:

The paramedics have packed their bags in a specific way. I don’t know how. When i start rifling around for the thing i need, i mess up the bag. That costs them time for this patient, then the next, then the next patient.

The humility is what surprised me. This was an expert knowing precisely when they needed to defer to another expert. They could do more harm than good, so they had to get out of the way. We should wish for more experts like this.